Discovering history

High-tech from Hordel

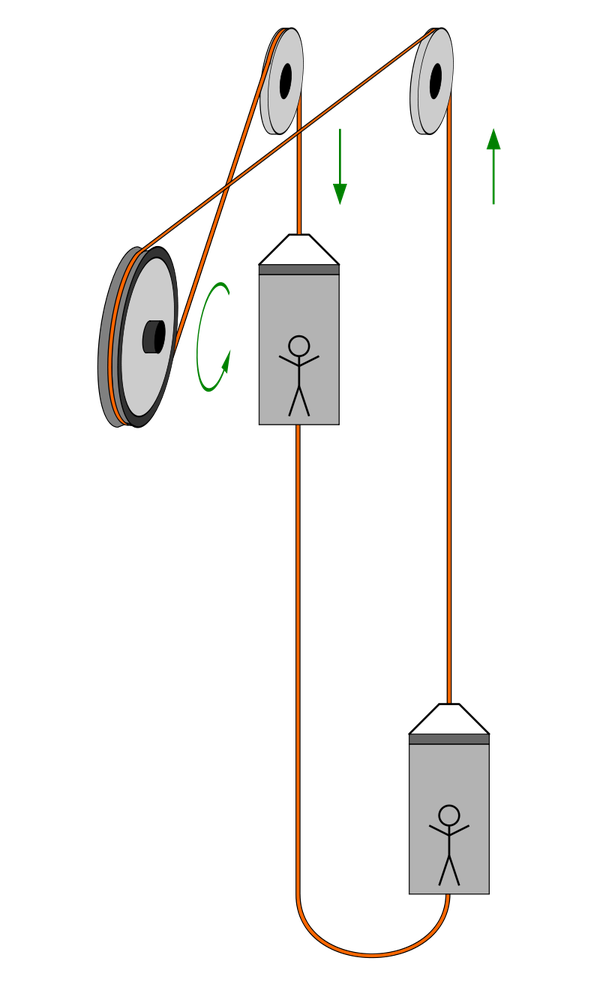

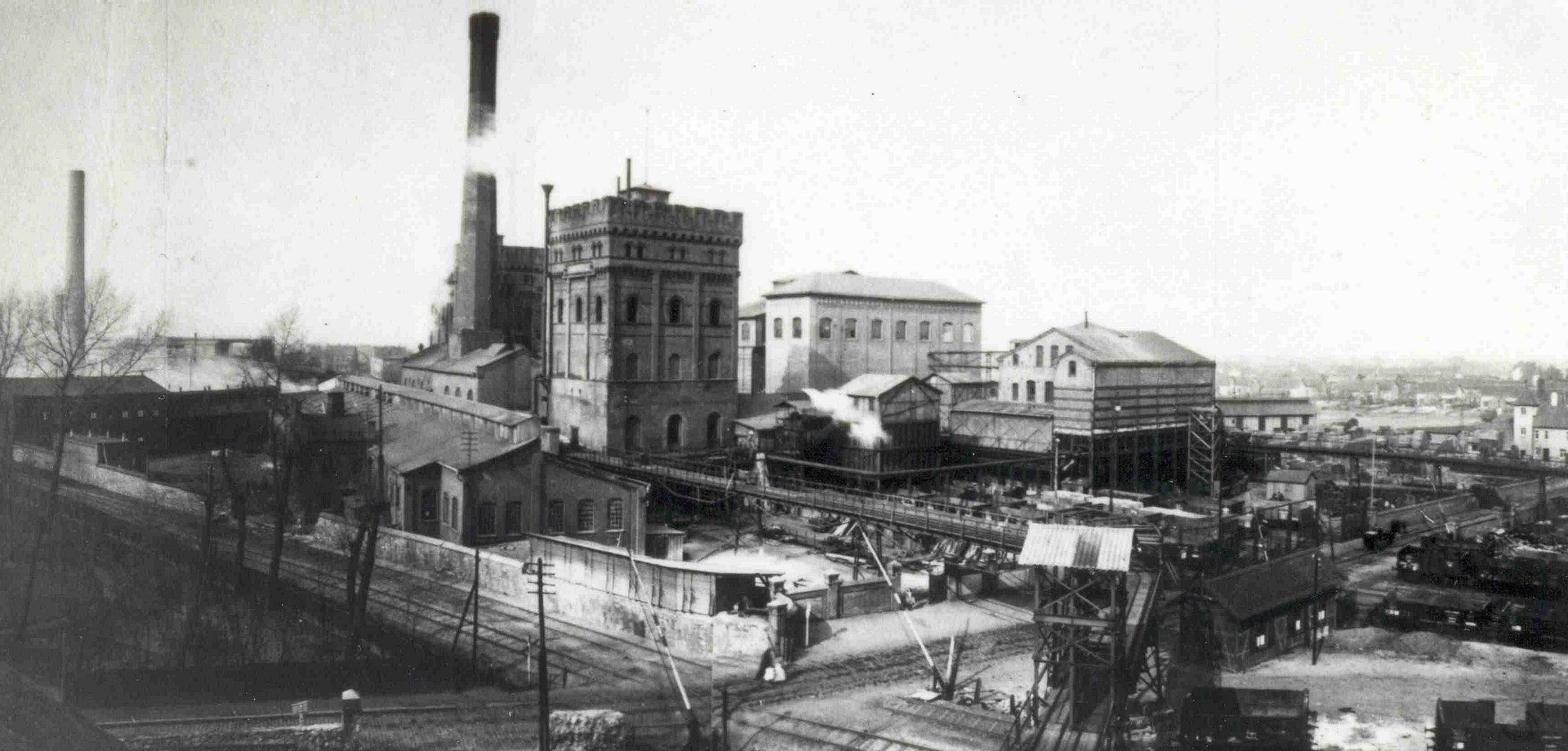

The Hannover colliery was set up in 1854. But it was not until it was taken over by the industrial tycoon from Essen, Alfred Krupp, that it really began to flourish. Within a matter of years it became a development centre for state-of-the-art technology. Here, in 1877 the mining director Friedrich Koepe invented a hauling system, now named after him, that was adopted all over the world. Later the first tower hauling gear and the first four-cable hauling system were developed at the Hannover colliery.

After the colliery was closed down in the 1970s following the crisis in the mining industry, most of the buildings and equipment on the site were demolished. The regional authority of Westphalia-Lippe then took over the site, listed the buildings and integrated them in its industrial museum. After costly restoration work had been completed the museum was opened to the general public for the first time in 1995. Necessary extensions have still to be made before it can be regarded as a complete museum in its own right.

Innovations - Conveyor technology for civil engineering

The piston rods set the huge flywheel in motion with a deep rumble, the covers on the valves begin to clatter and it smells of oil. Operating the steam hauling engine is a fascinating business. Today this amazing example of technological history is run by electricity instead of gas.

The heart of the Hannover Colliery beats in the engine house. The centre of miners’ lives, however, was outside the colliery gates. Our museum owns three large workers’ houses, each of which has a garden typical of its time. The houses give visitors a good impression of everyday life from the era of Kaiser Wilhelm to the miracle years of the 1950s.

Workers from Germany and abroad have been living on the housing estates of the Hannover colliery since the 1860s. They were attracted to the area by the prospect of making money quickly in exchange for hard work. In the early years the colliery was able to cover its employment requirements by recruiting works from the local area. After that, until the turn of the 20th century, the mining companies began to enlist Polish immigrants to cover their needs. After the Second World War “guest workers” from Italy to Turkey arrived to find work here.

Immigrant workers have left their mark on the region for over 150 years. We highlight their contribution to the history and everyday life of the Ruhrgebiet in a series of temporary exhibitions and events.

"Dahlhauser Heide"

The colliery, with its constantly growing demand for labour, initially attracted workers from Westphalia, Hesse and the Rhineland. In addition, immigrants from West and East Prussia, Silesia, Posen and Masuria found employment in Hannover.

After expanding the mine into a large-scale operation, Krupp had the Dahlhauser Heide colony built in 1907. His architect, Robert Schmohl, designed the workers' housing estate as a garden city with a central park. The 339 semi-detached houses were modelled on Westphalian farmhouses and had large gardens. This was in keeping with the lifestyle of the miners' families, who had mainly migrated from rural areas. The families grew their own vegetables and kept small animals to ensure they had enough to eat. In 1960, the first people arrived from Greece, followed soon afterwards by others from Italy, Yugoslavia, Turkey and Morocco.

End of an era

The Hannover colliery initially emerged victorious from the mining crisis that began in 1958: in 1967, Shaft II was expanded to become the central extraction shaft for all Bochum mines. In 1969, the Hannover colliery was incorporated into the newly founded Ruhrkohle AG.

However, the ongoing mining crisis soon brought an end to this: in 1973, the Hannover colliery was the last mine in the former mining town of Bochum to be closed down. In 1979, the industrial buildings were demolished. Only the oldest ones – the Malakow tower with the machine hall and the mine ventilation building – were preserved as industrial monuments. In 1981, the Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe (LWL) incorporated the Hannover colliery into its Westphalian Industrial Museum and restored the buildings. The monument has been open to visitors since 1995.